Opening Thoughts

THE CALL FOR THE STUDY OF HORROR IN THE RHETORICAL CANON

OPENING THOUGHTS

THE MATERIAL RHETORIC OF “MEIN HERZ BRENNT” VIDEO EDIT

THE MATERIAL RHETORIC OF “MEIN HERZ BRENNT” PIANO EDIT

CLOSING THOUGHTS

THE TWO VIDEOS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

OPENING THOUGHTS

THE MATERIAL RHETORIC OF “MEIN HERZ BRENNT” VIDEO EDIT

THE MATERIAL RHETORIC OF “MEIN HERZ BRENNT” PIANO EDIT

CLOSING THOUGHTS

THE TWO VIDEOS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

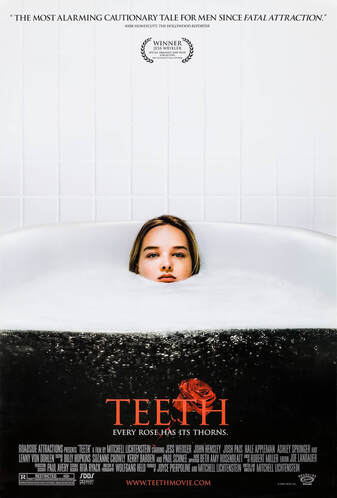

2007’s Teeth, a movie that features the vagina dentata folk story

2007’s Teeth, a movie that features the vagina dentata folk story

Why are we fascinated with horror? Horror permeates American culture for certain, but horror can also be seen in other cultures. With movies like Audition that examine the ethos of a society when it goes horribly wrong, or Ju-On and the Spanish film, Películas para no dormir: La habitación del niño (Films to Keep You Awake: The Baby’s Room) that explore cultural folklores, horror is not limited to America. In fact it seems foreign horror movies are more popular than ever—at least in my house. From the Russian Night Watch where forces of light and dark are pitted against each other to the child vampire in the Swedish original Låt den rätte komma in (Let the Right One In) to the atmospheric horror film, Muoi, that examines a Vietnamese legend, horror is a mainstay of popular culture.

But horror movies are not limited to obvious horror, the physical or mental torture of the characters. Horror has a long relationship with sexuality, specifically female sexuality. In movies like Carrie (1973) and Fascination, evil seductresses experiment with horrific events that are nonetheless laced with eroticism. But this eroticism is from a male-centric perspective. Even when the female character is the horror text’s victim, as in Strange Circus, male-defined sex is involved. In other words, sex geared towards pleasing men is the norm, even if the sex is between so-called lesbians. In Strange Circus, the protagonist is forced to witness her parents’ sex acts and then, later, endure sexual abuse from her father. Nonetheless, many horror movies are from the male perspective.

Laura Mulvey argues that because women are traditionally framed as the object for the male gaze, women characters are thusly Otherized. Camera shots linger on a woman’s curves or the woman’s body is less clothed, thereby implying a submissive status. Woman is recognized in her relationship to man. Since, according to Mulvey, the film’s narrative is typically told from a heterosexual male point of view, women viewers are thus conditioned to view other women—and themselves—from a heterosexual male point of view. Barbara Creed argues women in horror films are similarly relegated and defined in terms of their relationship to the male characters in the movies and to the male audience members or in terms of their reproductive functions and mothering. Creed also argues that an additional category of the monstrous woman is when she is the castrator. Thus, she becomes dangerous to the male characters or the male viewers. She inhabits a space that is nonetheless in relation to males.

So what might this tiny glimpse into horror films mean? Besides promising the “anticipation of terror, the mixture of fear and exhilaration as events unfold, the opportunity to confront the unpredictable and dangerous, the promise of relative safety (both in the context of a darkened theater and through a narrative structure that lasts for a finite amount of time and/or number of pages), [horror also promises] the feeling of relief and regained control when it’s over” (Fahy 11). This sense of danger within a controlled environment is what provides fascination—and a useful coping strategy. Those of us who are horror junkies thrive on the adrenaline horror provides knowing full well that the horrific event will end. Furthermore, as Philip J. Nickel argues in “Horror and the Idea of Everyday Life: On Skeptical Threats in Psycho and The Birds,” horror does indeed contribute to art and entertainment. From Shakespeare’s use of the uncanny or dread to a slasher movie’s use of graphic violence, horror has an appeal. Besides the use of the uncanny or dread, horror also provides windows into the multiple discourses resonating within a society.

Nickel also maintains “there is something good about horror…aesthetically interesting and epistemologically good” (26). He further argues that horror “gives us a perspective on so-called common sense [and that it] helps us to see that a notion of everyday life completely secure against threats cannot be possible,…that the security of common sense is a persistent illusion” (ibid).

In other words and to use Buffy slang, horror helps us to deal.

In the next section, I will discuss the material rhetoric of Rammstein’s “Mein Herz brennt” videos. By focusing on select bodies on display in the two videos, I aim to unpack the strategies of suasion in horror in the piano version and the video edit version of “Mein Herz brennt.”

But horror movies are not limited to obvious horror, the physical or mental torture of the characters. Horror has a long relationship with sexuality, specifically female sexuality. In movies like Carrie (1973) and Fascination, evil seductresses experiment with horrific events that are nonetheless laced with eroticism. But this eroticism is from a male-centric perspective. Even when the female character is the horror text’s victim, as in Strange Circus, male-defined sex is involved. In other words, sex geared towards pleasing men is the norm, even if the sex is between so-called lesbians. In Strange Circus, the protagonist is forced to witness her parents’ sex acts and then, later, endure sexual abuse from her father. Nonetheless, many horror movies are from the male perspective.

Laura Mulvey argues that because women are traditionally framed as the object for the male gaze, women characters are thusly Otherized. Camera shots linger on a woman’s curves or the woman’s body is less clothed, thereby implying a submissive status. Woman is recognized in her relationship to man. Since, according to Mulvey, the film’s narrative is typically told from a heterosexual male point of view, women viewers are thus conditioned to view other women—and themselves—from a heterosexual male point of view. Barbara Creed argues women in horror films are similarly relegated and defined in terms of their relationship to the male characters in the movies and to the male audience members or in terms of their reproductive functions and mothering. Creed also argues that an additional category of the monstrous woman is when she is the castrator. Thus, she becomes dangerous to the male characters or the male viewers. She inhabits a space that is nonetheless in relation to males.

So what might this tiny glimpse into horror films mean? Besides promising the “anticipation of terror, the mixture of fear and exhilaration as events unfold, the opportunity to confront the unpredictable and dangerous, the promise of relative safety (both in the context of a darkened theater and through a narrative structure that lasts for a finite amount of time and/or number of pages), [horror also promises] the feeling of relief and regained control when it’s over” (Fahy 11). This sense of danger within a controlled environment is what provides fascination—and a useful coping strategy. Those of us who are horror junkies thrive on the adrenaline horror provides knowing full well that the horrific event will end. Furthermore, as Philip J. Nickel argues in “Horror and the Idea of Everyday Life: On Skeptical Threats in Psycho and The Birds,” horror does indeed contribute to art and entertainment. From Shakespeare’s use of the uncanny or dread to a slasher movie’s use of graphic violence, horror has an appeal. Besides the use of the uncanny or dread, horror also provides windows into the multiple discourses resonating within a society.

Nickel also maintains “there is something good about horror…aesthetically interesting and epistemologically good” (26). He further argues that horror “gives us a perspective on so-called common sense [and that it] helps us to see that a notion of everyday life completely secure against threats cannot be possible,…that the security of common sense is a persistent illusion” (ibid).

In other words and to use Buffy slang, horror helps us to deal.

In the next section, I will discuss the material rhetoric of Rammstein’s “Mein Herz brennt” videos. By focusing on select bodies on display in the two videos, I aim to unpack the strategies of suasion in horror in the piano version and the video edit version of “Mein Herz brennt.”

The Rhetoric of Rammstein by Lisette Blanco-Cerda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.