THE MATERIAL RHETORIC OF “MEIN HERZ BRENNT” VIDEO EDIT

THE CALL FOR THE STUDY OF HORROR IN THE RHETORICAL CANON

OPENING THOUGHTS

THE MATERIAL RHETORIC OF “MEIN HERZ BRENNT” VIDEO EDIT

THE MATERIAL RHETORIC OF “MEIN HERZ BRENNT” PIANO EDIT

CLOSING THOUGHTS

THE TWO VIDEOS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

OPENING THOUGHTS

THE MATERIAL RHETORIC OF “MEIN HERZ BRENNT” VIDEO EDIT

THE MATERIAL RHETORIC OF “MEIN HERZ BRENNT” PIANO EDIT

CLOSING THOUGHTS

THE TWO VIDEOS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

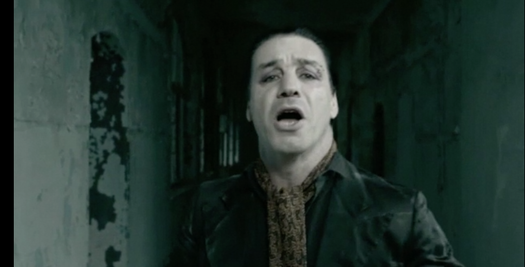

Till Lindemann as the storyteller persona in the video edit version of “Mein Herz brennt”

Till Lindemann as the storyteller persona in the video edit version of “Mein Herz brennt”

Material rhetoric holds multiple definitions. For the sake of this web essay, though, I will focus on the following provided by Dr. Angela Haas: the material conditions of the two videos as made product and the delivery mechanism vis-à-vis music video. While I will not assess all five canons (invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery), I will concentrate on arrangement, style, and delivery in the multi-mediated rhetoric of the two music videos.

Aristotle argues that nature can take one only so far. Thus, the concept of performativity arises. When one performs, one adopts a persona, which introduces nothingness on which somethingness is based. If one takes away the mask, nothing remains. Therefore, all there is is a series of performances. And so it goes with the two versions of the same Rammstein song.

The two video versions of the same song, “Mein Herz brennt,” form a unified narrative. The invented narrative of both the lyrics(1) and the videos center on an intersection of a frightful folk tale and a German children’s television show, Das Sandmännchen. While this 1950s-era television show featured a kindly stop motion puppet storyteller, Rammstein’s storyteller personas are simultaneously seemingly benign and horrific.

In the video edit version of “Mein Herz brennt” the sandmännchen storyteller, portrayed by Rammstein’s lead singer Till Lindemann, appears to be a benign yet pained man. His materiality is one of tasteful yet conservative clothes and riding boots that suggest a bygone, somewhat romantic era. His anachronistic eyebrow piercings convey a passion, one that suggests a punk disregard for societal mores and expectations.

Yet the passion that is evidenced in his facial expression and body language suggest an urgency of which the reason the audience does not yet fully understand. This storyteller version is persuasive in his angst-filled features, open mouth that echoes a pain-filled groan, forward-thrust chin so that the eyes gaze downward at the video’s audience, and tensed shoulders. The video edit storyteller’s body and materiality heighten the textual rhetoric of the song by “giving way to a strong emphasis on passion and imagination” (Hawhee and Holding 266). During this scene, Lindemann repeatedly sings, “Mein herz brennt,” which translates to “My heart burns.”

Aristotle argues that nature can take one only so far. Thus, the concept of performativity arises. When one performs, one adopts a persona, which introduces nothingness on which somethingness is based. If one takes away the mask, nothing remains. Therefore, all there is is a series of performances. And so it goes with the two versions of the same Rammstein song.

The two video versions of the same song, “Mein Herz brennt,” form a unified narrative. The invented narrative of both the lyrics(1) and the videos center on an intersection of a frightful folk tale and a German children’s television show, Das Sandmännchen. While this 1950s-era television show featured a kindly stop motion puppet storyteller, Rammstein’s storyteller personas are simultaneously seemingly benign and horrific.

In the video edit version of “Mein Herz brennt” the sandmännchen storyteller, portrayed by Rammstein’s lead singer Till Lindemann, appears to be a benign yet pained man. His materiality is one of tasteful yet conservative clothes and riding boots that suggest a bygone, somewhat romantic era. His anachronistic eyebrow piercings convey a passion, one that suggests a punk disregard for societal mores and expectations.

Yet the passion that is evidenced in his facial expression and body language suggest an urgency of which the reason the audience does not yet fully understand. This storyteller version is persuasive in his angst-filled features, open mouth that echoes a pain-filled groan, forward-thrust chin so that the eyes gaze downward at the video’s audience, and tensed shoulders. The video edit storyteller’s body and materiality heighten the textual rhetoric of the song by “giving way to a strong emphasis on passion and imagination” (Hawhee and Holding 266). During this scene, Lindemann repeatedly sings, “Mein herz brennt,” which translates to “My heart burns.”

A forbidding expression of the storyteller in the video edit version of “Mein Herz brennt”

A forbidding expression of the storyteller in the video edit version of “Mein Herz brennt”

His storyteller persona is also menacing. Singing the lyrics, “Nun liebe Kinder gebt fein acht / ich bin die Stimme aus den Kissen / ich hab euch etwas mitgebracht / ein heller Schein am Firmament,”(2) the video edit’s storyteller stalks the caretaker when she is both young and old. The lyrics, coupled with his deep, slightly guttural voice echo a children’s fairy tale but with a disturbing twist. He invites his listeners—the “liebe Kinder” (dear children) he names and those of us who listen to the song—to pay attention. This invitation to pay attention is a classic narrative convention. The storyteller calls his (or her) listeners in to listen closely, often physically moving their bodies closer to the storyteller in order to better hear the story. Audience members are commanded to “HWÆT” in Beowulf’s Old English or to “Listen!” and “Hear me!”(3) in modern English translations of the epic. Employing a much subtler, yet equally invitational strategy, Seamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf’s opening of “So.” invites the listeners to respond with “so what?” The audience is now engaged with the storyteller by asking what happens next. These concise openings that directly address the listeners to do something, to pay attention, is a powerful rhetorical strategy that does not lose its power in this song. In fact, Lindemann’s deeply resonant and alternately rough and smooth baritone effectively entice listeners to physically move in closer.

A menacing storyteller and frightened caretaker in the video edit version of “Mein Herz brennt”

A menacing storyteller and frightened caretaker in the video edit version of “Mein Herz brennt”

The video edit’s storyteller’s menacing body language consisting of slumped shoulders and implied heavy steps persuade the old woman caretaker—along with the video’s viewers—that this being, this particular storyteller is something to fear. The two characters’ outlines are stark against the tattered pale wall behind them. This storyteller’s spiritual or otherwise intangible heaviness is emphasized while the old woman’s fear becomes redolent in her pinched frame. She seems to actively try to fold herself in as if she is consciously trying to disappear.

Thus, both characters’ gestures “receive impressions” that are formed by the “sharpness or dullness of passion” (Hawhee and Holding 288). Lindemann’s heavy gait barely confines the threatened horror his storyteller promises, while the old woman’s shrinking frame barely confines her desperate fear.

Thus, both characters’ gestures “receive impressions” that are formed by the “sharpness or dullness of passion” (Hawhee and Holding 288). Lindemann’s heavy gait barely confines the threatened horror his storyteller promises, while the old woman’s shrinking frame barely confines her desperate fear.

The fact that both video versions were filmed at Beelitz-Heilstätten, a group of buildings that have been used as a sanatorium and hospital and wherein, legend has it, murder(s) have been committed(4), further construct a tone of horror. The two videos were filmed in abandoned and derelict portions of Heilstätten and, as a result, the setting and the building’s history strengthen the ethos of the perverse storyteller, who is necessarily inflicting harm and fear on the children under the care of the young woman/old woman.(5) This storyteller, presumably the ultimate bogeyman that hides beneath the bed, seems to not take pleasure when he inflicts terror on his victims. He simply performs what he must do.

Acting as further evidence to the storyteller’s status as bogeyman, specifically a supernatural one, is this scene when the storyteller advances and, ultimately, claims the old woman. This claiming is suggestive of the ever-present horror in a human’s life and the inability to truly escape such horror. Throughout the video, viewers witness this caretaker changing in age. She is seen as young and then old in the same scene.

Acting as further evidence to the storyteller’s status as bogeyman, specifically a supernatural one, is this scene when the storyteller advances and, ultimately, claims the old woman. This claiming is suggestive of the ever-present horror in a human’s life and the inability to truly escape such horror. Throughout the video, viewers witness this caretaker changing in age. She is seen as young and then old in the same scene.

Besides suggesting the storyteller is supernatural because he does not age, this juxtapositioning of ages also suggests that this struggle between the caretaker and the storyteller has been going on for quite some time. Time does not affect the storyteller. Whereas the children’s caretaker ages, the storyteller-cum-bogeyman does not. Timelessness is implied, further suggesting that even in when a new caretaker comes to the building, the storyteller will still be there and the struggle will continue.

In the next section, I will discuss the storyteller’s changing persona in the Piano Edit version of “Mein Herz brennt.”

(1) Because my German is woefully lacking, I am relying on the translations provided by Jeremy Williams at his site, Herzeleid.

(2) This translates to: “Now, dear children, pay attention / I am the voice from the pillow / I have brought you something / a bright light on the heavens.”

(3) An interesting article in The Independent explores the possible mistranslations of this exact opening.

(4) In The Making of “Mein Herz brennt,” the band members explore the history of the buildings, with Till Lindemann talking about the murders.

(5) The lyrics tell of demons and ghosts that come out at night in order to draw tears from sleeping children. These tears then are injected into the creature’s “kalten Venen,” or cold veins. It becomes obvious that children’s tears are the sustenance for this monster.

In the next section, I will discuss the storyteller’s changing persona in the Piano Edit version of “Mein Herz brennt.”

(1) Because my German is woefully lacking, I am relying on the translations provided by Jeremy Williams at his site, Herzeleid.

(2) This translates to: “Now, dear children, pay attention / I am the voice from the pillow / I have brought you something / a bright light on the heavens.”

(3) An interesting article in The Independent explores the possible mistranslations of this exact opening.

(4) In The Making of “Mein Herz brennt,” the band members explore the history of the buildings, with Till Lindemann talking about the murders.

(5) The lyrics tell of demons and ghosts that come out at night in order to draw tears from sleeping children. These tears then are injected into the creature’s “kalten Venen,” or cold veins. It becomes obvious that children’s tears are the sustenance for this monster.

The Rhetoric of Rammstein by Lisette Blanco-Cerda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.